What is accrued income?

To understand what accrued income is, first it is helpful have a clear understanding of what interest is.

Interest is, effectively, a charge a borrower pays for borrowing money. The interest payments act as compensation for lenders temporarily parting with their money and taking on the risk of non-repayment by the borrower. In the UK, when an individual receives interest payments, they must pay Income Tax on the amounts.

Interest payments are generally made at regular and known dates within a given period. As a result, between interest payment dates, a lender is seen as having accrued income as there is the expectation that they will receive an interest payment.

How is accrued income calculated?

The way accrued income is calculated is far from straightforward, but let us explain:

The gross interest payment is simply the annual amount of interest due divided by the number of payments in that year. So, if someone had bought a 5% UK Treasury Bond 2028 for £10,000, the annual interest would be £500. If this were to pay out twice a year, the gross interest payment would therefore be £250.

The ‘A’ and the ‘B’ in our equation is where things get more complicated.

Let’s take the easier part first. ‘B’ is equal to the number of days in the interest period, as measured from the day after one payment date to the next interest payment date.

So, taking our example of the 5% UK Treasury Bond 2028. Let’s say its first payment date was 15 January and its second payment date was 15 July. This means its interest period between these dates in 2025 would be 181 days, counting from 16 January to 15 July inclusively.

‘A’ in this equation can be one of two things depending on when in the year the bond was transferred and whether it was transferred ex- or cum-dividend.

Ex-dividend vs Cum-dividend

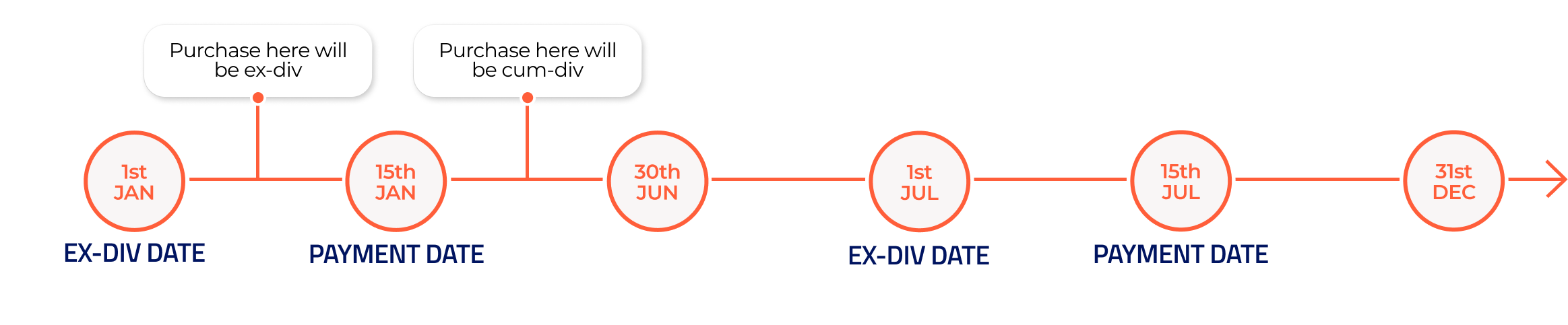

Ex-dividend, commonly shortened to ex-div, means an investor has bought a security without entitlement to the next interest payment. Cum-dividend, or cum-div, means an investor has bought a stock with entitlement to the next interest payment.

Whether an investor is entitled to the payment will depend on the ex-div date of the security. The ex-div date is essentially the cutoff date for an investor to receive a payment.

So, returning to our 5% UK Treasury Bond 2028 example.

Let’s say the ex-div dates for the bond are 1 January and 1 July. This means the last point at which an investor could buy the bond and receive the next interest payment would be the end of the day on 31 December for the payment on 15 January or 30 June for the payment on 15 July.

Cum-dividend

When someone transfers a security cum-div, then the ‘A’ in our equation equals the number of days from the day following the last interest payment to the transfer date.

So, if someone bought the 5% UK Treasury Bond 2028 on 17 March, they have long missed the bond’s January pay out but would be entitled to the next payment on 15 July. This would make their purchase cum-div, meaning they’d need to start counting from 16 January to 17 March, which is equal to 61 days.

Their accrued income would therefore be 61/181 × £250 which is equal to £84.25.

Ex-dividend

If the security was transferred ex-div, the ‘A’ in our equation will be equal to the number of days from the day after the bargain date to the next interest payment.

Taking our 5% UK Treasury Bond 2028 example again: if an individual were to buy the bond on 7 January, they would have to start counting from the day after the purchase until the next interest payment on 15 January. This would be 8 days.

Their accrued income would therefore be 8/181 x £250 which is equal to £11.05.

How is accrued income treated when a security is bought or sold, and how is it taxed?

The value of an interest-bearing security may go up as the date of the next interest approaches. This is because the buyer will see an immediate return of some of the price they paid, while the seller ensures that they do not lose on the interest they would have received if they had held the security a little longer.

In the UK, if the buyer is entitled to the next payment (a transfer cum-div), a buyer can get tax relief on this extra amount paid under the Accrued Income Scheme. The extra amount paid, known as the ‘accrued income loss’, can be deducted from the interest that they will receive when the security next pays out. However, it also must be deducted from their purchase cost to reflect the fact that it will be paid back to them. The seller will carry out the reverse adjustments, deducting the accrued income amount from their sale proceeds and adding it to their income for the year.

If the seller, not the buyer, is entitled to the next interest payment (a transfer ex-div), things are a little different. This is because when the seller is entitled to the next interest payment, the buyer will often be purchasing the security for a lower price, with the benefit of several days of interest accrued for the payment after.

In this scenario, the seller will be taxed on the interest payment but will be able to claim an accrued income loss for the interest accrued that they will not receive. This amount can be deducted from the interest they do receive. The person buying the security would have an accrued income profit of an equivalent amount.

When does the Accrued Income Scheme apply and who can use it?

The Accrued Income Scheme is triggered by a transfer. This is usually a sale, but it could also be an exchange, a gift, or similar event deemed to be a transfer in the eyes of HMRC.

The scheme only applies to individuals, trustees of trusts and the personal representatives of a deceased individual. Companies are not subject to the Accrued Income Scheme. Instead, they pay corporation tax on interest under the loan relationships’ rules.

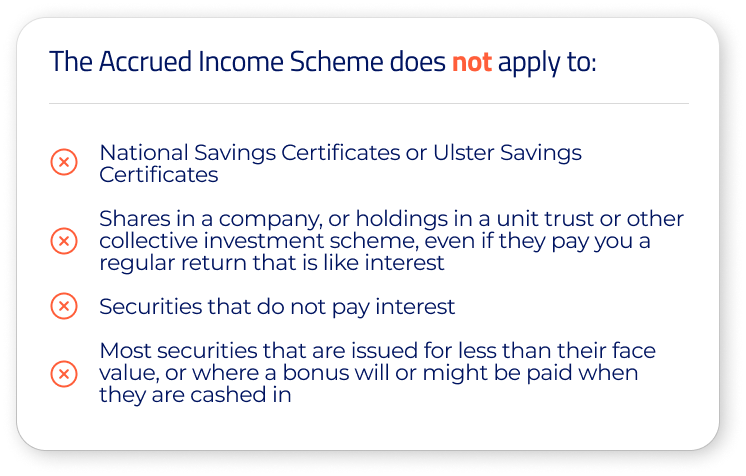

The securities covered by the Accrued Income Scheme include gilts issued by the UK government, investment bonds issued by banks or building societies, and bonds/loan notes/debentures/alternative finance investment bonds issued by UK companies/local authorities/other similar bodies.

Similar securities issued by overseas companies or governments also fall under the Accrued Income Scheme, but any adjustments will need to be reported as foreign income or gains on the investor’s tax return.

A fund such as a unit trust scheme or open-ended investment company (OEIC), for example, may distribute income which is treated as interest because greater than 60% of the fund’s underlying assets are interest-bearing assets like bonds. These funds do not come under the Accrued Income Scheme, however.

What about deeply discounted securities?

Deeply discounted securities are a type of bond where an investor receives their return by way of a discount on the purchase price versus the redemption price. These bonds don’t usually make any distributions, but some do. They are specifically excluded from the Accrued Income Scheme, nonetheless. This means that the price paid on any trades is not adjusted for any income accrued up until that point because no income has accrued.

The Accrued Income Scheme and capital gains tax

When an interest-bearing security is transferred under the Accrued Income Scheme, the accrued interest is treated as income rather than as part of the transfer consideration. This means that the interest will not be subject to capital gains tax (CGT).

If there was an accrued income adjustment made on acquisition of the security, this must be taken into account when computing the allowable cost on disposal.

Many of the securities covered by the Accrued Income Scheme will be exempt from CGT anyway as they are either gilts or Qualifying Corporate Bonds.

How does CGiX handle accrued income?

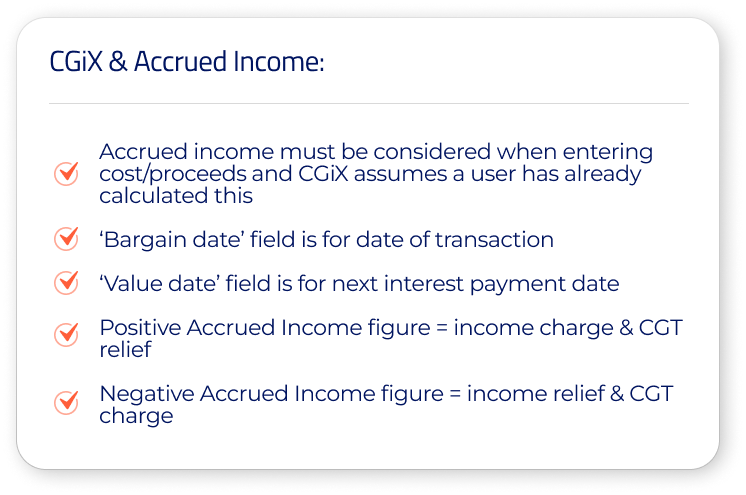

CGiX helps financial advisers determine whether their client will be subject to an income or capital gains tax charge when they sell or buy an interest-bearing security such as a bond or gilt.

Our software will assume that a user has already computed their client’s overall accrued income as part of their calculations. So, it is important to include this amount when entering cost/proceed figures into CGiX.

Users are invited to enter the date of transaction in the ‘bargain date’ field and the date of the next interest payment in the ‘value date’ field. Once this has been entered, CGiX can then calculate whether the investor will receive income or a capital gains tax charge.

If CGiX returns a positive accrued income figure, then it has been calculated that the investor is subject to an income charge and CGT relief. If CGiX returns a negative figure, then the investor would be subject to a CGT charge and income relief.

How does CGiX handle deeply discounted securities?

When handling a deeply discounted security in CGiX, we will simply take the proceed and cost figures given by the user without making any adjustment.

One thing to note, however, is that where a deeply discounted security was bought on or after 27 March 2003, any loss on disposal is not considered an ‘allowable loss’. If the deeply discounted security was bought before this date, however, a loss may be considered an allowable capital loss – though there are conditions to this.

In CGiX, losses on deeply discounted securities are listed separately to ordinary allowable losses for all transactions. This information is provided for the benefit of the investor or their financial adviser to complete their tax return with the highest degree of accuracy.